Week 10 – 11 September 2016:

Waste Not, Want Not

The efforts of dedicated biologists enlarge our understanding of bird biology with their discoveries. After years of work in the field and laboratory, results are published in the pages of scholarly journals so that they can illuminate others, now and into the future. That is one of the interesting things about scientific journals – with any luck, their contents will continue to be available to researchers for centuries to come.

I recently pulled a ninety-year old copy of the journal The Condor: A Magazine of Western Ornithology off a shelf in my personal library. The copy was Issue 1 of Volume 28. Along with journals like Ibis and The Auk, it represented a repository of the best new findings of bird enthusiasts, with particular emphasis on the west coast of North America.

By today’s standards, much of the content of the 56-page copy in my hand would be considered natural history, rather than science. The first thirty pages were a consideration of bird husbandry in British aviaries, written by Casey Wood of Kandy, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). This was followed by short pieces on the appearance of Franklin Gulls in Colorado, the consumption of frozen insects by American Dippers, and the vocal behaviour of Band-tailed Pigeons. One article was particularly revealing, not just of the birds being studied, but also of the writer.

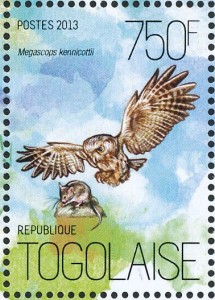

Ernest D. Clabaugh explained that he had been engaged in banding (“ringing” in the UK) nestling Western Screech-owls. He noted the remains of meals brought by the parents to their chicks. Most of these were House Sparrows, supplemented by gophers, mice and salamanders. “It is interesting to note,” wrote Clabaugh, “that practically all of the birds found in the nest had their heads eaten off when I found them.”

Even more interesting to me is Clabaugh’s honesty. At 05:30 on 3 June, 1924, he dropped one of the young owls while banding it. The bird appeared to be injured, but he applied band number 223576, and put it back in the nest. When Clabaugh returned to the nest the next day: “the leg of no. 223576, which held the band, was all that was left of this bird. It was in the nest, the bird apparently having been eaten by the three remaining young owls.”

I found a few details of the life of Clabaugh. A resident of Berkeley, he trained as a civil engineer at the University of California, but his great joy appeared to be the lives of birds. Over a period of 30 years, Clabaugh banded many thousands of birds, an activity he continued to his death in 1953. He served on the executive of the Western Bird Banding Association, and the Cooper Ornithological Club, the group that published The Condor. He was also a very honest man.

Clabaugh, E. D. 1926. Notes of the food of the California Screech Owl. Condor 28:43-44.

Photo credits: Western Screech Owl, Oregon Zoo – www.oregonzoo.org; Western Screech Owl stamp – www.pinterest.com