Week 20 – 27 November 2016:

Then and Now

Many fields of scientific endeavour have changed dramatically in my lifetime. New technologies have allowed great advances in astronomy, physics, chemistry, and some branches of biology. Ornithology less so. I think the reason is that biologists studying birds acquired most of the tools that they needed early on. Binoculars, a notebook and pencil, a rain jacket and hat… What else do you need?

It is true that our capacity to track individual birds has increased greatly as a result of advances in transmitter technology, but many studies continue to use nothing more sophisticated than numbered aluminum leg bands. Progress in gene sequencing has allowed us to leap forward in our understanding of evolutionary relationships among birds groups, but ornithologists still return to museum collections to measure stuffed specimens.

If we go further back in the history of ornithology, differences between then-and-now become more apparent. Papers concerning bird biology published a century ago were far less numerical than they are today, and statistical analysis of data was rare. It also seems to me that research then was less likely to be directed at answering fundamental questions.

For more than 130 years, The Auk has been one of the three great journals dedicated to research on birds. In the January 1916 issue was an article by Henry J. Fry concerning seasonal declines in birdsong. The study was conducted at the field station at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, New York. Although Fry was not absolutely clear, it seems that he was teaching a course in ornithology at Cold Spring, and had his students collect observations. The songs of birds were noted each day between 06:00 and 07:30, and between 10:00 and 11:30, in addition to alternating afternoons. The study ran from July 1 to 10 August.

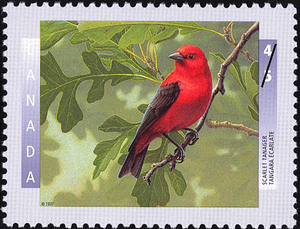

One by one, Fry described the lessening of singing by birds as the season progressed. “The Scarlet Tanager (Piranga erythromelas)” wrote Fry, “was in full rich song till about July 16, though further study may show this day to be inaccurate by several days. From that time on the song declined steadily and the last one was recorded on the twenty-seventh.”

“The Wood Pewee (Myiochanes virens) began its decline almost imperceptibly around July 20, and from that day it gradually became less and less, though the daily diminution was scarcely evident.” And that was that. Fry did not speculate about the cause of seasonal variation in the volume and frequency of singing, nor about possible reasons for species’ differences in behaviour. It wasn’t science. At best it was natural history.

But consider this… It appears that global climate change may be causing some birds to alter their behaviour, such that they breed earlier in the year. In 1914 Henry Fry generated a systematic data set of the singing behaviour of more than two dozen species of birds. In doing so, he created an opportunity. A dedicated student of birds could reproduce Fry’s study to look for changes more than 100 years later. The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory is still there to facilitate study.

My efforts to find out more about the life of Henry Fry have resulted in little success. He may have been at Columbia University in some capacity in the 1890s. He appears to have been an associate member of both the American Ornithologists’ Union and the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club at the time he wrote his paper on singing behaviour. He may eventually be commemorated by a student keen to replicate his work. Are there any takers?

Fry, H. J. 1916. A study of the seasonal decline of bird song. Auk 33:28-40.

Photo credits: Scarlet Tanager stamp - colnect.com; Wood Pewee – www.birdfreak.com