To me, curlews, turnstones, sandpipers and snipe all look the same, varying only in their size. They all have long bills, reasonably long legs, and cryptic plumage. They wade in shallow water, and use their long bills to find food in the mud beneath their feet. Show me a bird enthusiast with a particular fondness for shorebirds, and I will show you someone who likes a challenge.

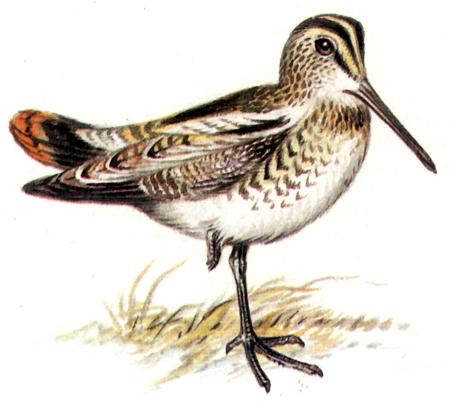

This isn’t a particularly charitable view, I suppose, but it seems reasonably astute. Take the Latham’s Snipe, for instance. The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia by Simpson and Day describes the body as cryptically mottled, the belly as pale, and the crown, eye-stripe and cheek stripe as dark brown. In the non-breeding season, Latham’s Snipes get even plainer.

This lack of pizzazz doesn’t mean that Latham’s Snipe doesn’t perform important ecological roles, nor that we can afford to ignore their long-term security. Luckily, the species isn’t currently threatened, with a global population estimated at between 25,000 and 100,000 individuals, but its numbers are in decline. According to the IUCN, the principal reasons for the bird’s decline are the destruction and degradation of its habitat. And what about global climate change? Are long-term changes in weather having an impact of the natural history of Latham’s Snipe?

David Wilson, Birgita Hansen, Jodie Honan and Richard Chamberlain, all residents of the state of Victoria in southeastern Australia, recently reported on their analysis of a wonderfully thorough data set. Latham’s Snipe breeds in Japan and far eastern Russia, but migrate to eastern Australia for the non-breeding season. Given that mean annual temperature and rainfall on the breeding grounds in Japan, and in the non-breeding areas in Australia, have changed significantly over the last century, Wilson and his colleagues asked whether Latham’s Snipe has altered the timing of its arrival in Australia.

The researchers used a range of sources of information, with particular reference to New South Wales (NSW) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). They scoured newspaper reports of the birds taken by hunters from 1846 to 1940. Thereafter, records of the first arrivals of Latham’s Snipe were taken from the Atlas of Living Australia, as well as newsletters, annual reports, and postings to online discussion groups devoted to birds.

The first reports of Latham’s Snipes in NSW and the ACT came as early as 30 July and as late as 23 September, with an average date of 14 August. Wilson et al. found no significant change in the arrival date over the 170 year study period. Although the first bird reported each year was not necessarily the very first individual to arrive, there is likely a strong correlation between the dates. In years gone by, a measure of honour befell the hunter who shot the first snipe of the season. More recently, dedicated bird enthusiasts have kept detailed records, and have been pleased to share their observations. The data are also likely to be skewed toward failed breeders who likely leave the breeding grounds before more successful individuals. Even so, the observations collected appear to represent a solid set.

Year-to-year variation in the timing of the first Latham’s Snipe in NSW and the ACT are likely to result from conditions on the breeding grounds and stopover areas. Even so, over the past 170 years, the long term average has not changed significantly. Are there comparably long-term data sets in your part of the world that might yield interesting findings about the timing of the lives of birds?

Wilson, D., B. Hansen, J. Honan and R. Chamberlain. 2017. 170 years of Latham’s Snipe Gallinago hardwickii arrivals in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory show no change in arrival date. Australian Field Ornithology 34: 76-79.

Photo credits: Latham’s Snipe drawing - http://animal.memozee.com/ArchOLD-6/1188176402.jpg & Wikipedia; Latham’s Snipe stamp - www.hipstamp.com