Falling Down the Thames Blog 52, 11th March 2015

The Chemistry of the River Thames

At the dawn of the 1970s, as I was struggling to understand my place in the big wide world, it seemed that my residency in the world might be rather brief. The covers of newsmagazines all shouted about the harm humankind was doing to Earth’s soil, air and water. The claim was made, again and again, that if we didn’t reduce our release of pollutants, we could all expect to be poisoned to death in reasonably short order. Something had to be done.

And something was done. We cleaned up the world. Much of the credit is due to youngsters who insisted that they be handed a planet with a future.

William Cox Bennett (1820-1895) was an English journalist and watchmaker. He composed a poem entitled Thames, the River – The Glories of Our Thames which I find particularly noteworthy in a discussion of the cleanliness of the world. It includes the lines:

O, clear are England’s waters all, her rivers, streams and rills,

Flowing stilly through her valleys lone and winding by her hills;

But river, stream, or rivulet through all her breath who names,

For beauty and for pleasantness with our own pleasant Thames.

Isn’t that nice? Well, things haven’t always been that way.

Over its two thousand year history London has had its share of pollution issues. In a fabulous book entitled The Restoration of the Tidal Thames by Leslie Wood, I learned the history of the problem. Wood wrote that when London was first developing as an urban entity, each home had sufficient land to enable people to bury their waste. But as the city’s population grew denser, this abundance of land was no longer available. Getting rid of waste by burning it wasn’t an option because of the risk of fire in a city built almost entirely of combustible materials. Much of the city’s household garbage and toilet waste was dumped into streets which drain into freshwater rivers that flowed through the city. Some waste went directly into the River Thames, even when laws were enacted to prevent it.

In 1375 Edward III journeyed down the River Thames and found it to be so foul that he asked London administrators to halt the practice of disposing of waste in streets and waterways. It is reported that Charles I was similarly disgusted with the state of city in 1628. Writer Ben Jonson (1572-1637) was so put off by the state of London’s River Fleet that he wrote:

In the first jawes appeared that ugly monster,

Ycleped Mud, which, when their oares did once stirre,

Belch’d forth an ayre as hot as the muster

Of all your night tubs, when the carts doe cluster,

Who shall discharge first his merd-urinous load.

Blech!

Somehow, despite centuries of abuse, the River Thames remained a comparatively healthy place for aquatic life. In the twelfth century, fish made up a substantial part of the diet of Londoners. If a 1457 report is to believed, whales, walrus, and even narwhals were being harvested from the tidal Thames. Trout, salmon, perch, pike and eels were all taken from the great river until the early 19th century.

But then things went wrong for the River Thames. Really wrong. I will write about that black period in Thames history in a later blog.

- Glen

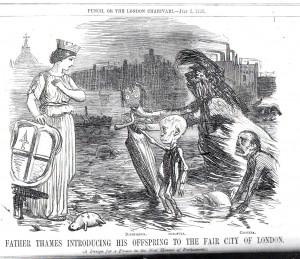

Photo credits: The Thames at Horseferry, by Dutch artist Jan Griffier - bjws.blogspot.co.uk; “Father Thames Introducing His Offspring to the Fair City of London.” Punch, or the London Charivari; July 3, 1858; pg. 5 - victoriancontexts.pbworks.com