Week 5 – 07 August 2016:

Perhaps We Should Begin Again

It is easy to be captivated by the extraordinary efforts of some birds in constructing their nests. Several days are required for a pair of Cliff Swallows to gather the 1000 mud pellets necessary to build their gourd-shaped nest under a bridge. A male Australian Brush-turkey will continue to maintain and modify his mound of rotting vegetation week after week, for as long as there are eggs to be incubated within it. And if nests can be so very costly to construct, why are members of some species willing to abandon a nest before ever using it?

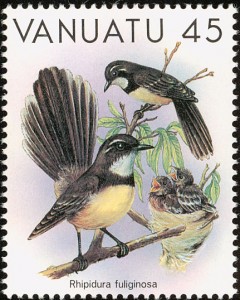

Christa Benkmann of Deakin University in Australia and Kathy Martin of the University of British Columbia in Canada addressed the question of nest abandonment in Grey Fantails, tiny, insect-eating songbirds native to Australia and New Guinea. Their nests are composed of dry grass and bark, enclosed within a layer of spider webs, with an open top and a stem hanging from the bottom. Fully 71% of nests appear to be abandoned before being used, and a few birds might build as many as seven nests in a breeding season. What is the point of constructing a nest just to abandon it?

Benkmann and Martin examined four possible explanations by monitoring the construction of 194 Grey Fantail nests in the 2012/2013 breeding season.

1. Could it be that what we have interpreted as abandonment was actually “cryptic predation?” Perhaps predators are sneaking in and consuming the eggs before the nest was noticed by researchers. This doesn’t seem to be the case in Grey Fantails, as most nests are abandoned before being completed.

2. Perhaps nests are abandoned after being damaged by extreme weather. Possible, but not likely, as Beckmann and Martin found that only 9% of abandonments occurred within 24 hours of bad weather.

3. Could it be that Grey Fantails are constructing decoy nests in order to dissuade potential predators? If a predator investigated one nest after another but didn’t find anything to eat, perhaps it would abandon its search for nests of that sort. This doesn’t seem likely in the case of fantails as some individuals were seen to dismantle abandoned nests, and reuse old nesting material in the construction of new nests.

4. Only one explanation was consistent with the observations of Beckmann and Martin. It seems that Grey Fantail nests that were under construction, but proved to be poorly concealed from predators, were abandoned. New nests were then constructed in more secure circumstances. Bird predators, particularly Pied and Grey currawongs were observed preying on both eggs and nestlings. As visual predators, superior nest concealment is probably essential to avoiding them.

But what actually cues the fantails, telling them that their current nest might not be in the right place? When contacted, Beckman responded that for daytime predators like currawongs, seeing them near the nest is probably enough to cause fantails to abandon the attempt. “I think mammalian predators might also find the nests after dark – maybe they leave scent cues the birds can use?” Beckman is planning to continue her work in this area, using cameras to identify predators at the nest. Very little is known about nest predators in Australia.

Beckman, C. and K. Martin. 2016. Testing hypotheses about the function of repeated nest abandonment as a life history in a passerine bird. Ibis 158:335-342.

Photo credits: incubating grey fantail - strathbogierangesnatureview.wordpress.com; stamp – www.birdtheme.org