Welcome to A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers. Visit here for weekly updates on the most exciting recent discoveries from the world of bird biology. Your adventure begins below!

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 108 -

Every Bird in the World

18 November 2018

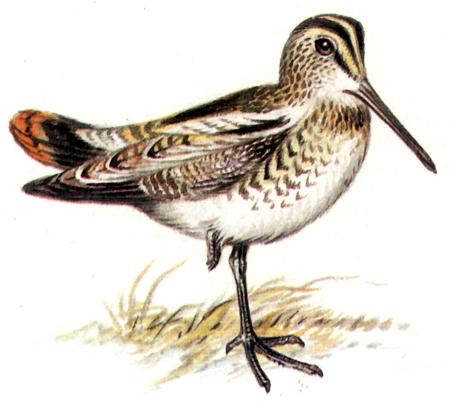

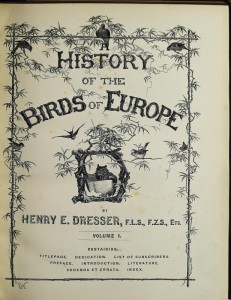

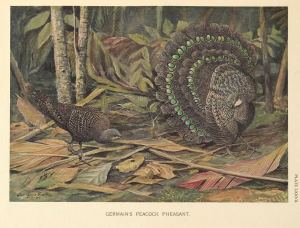

We share the planet with more than ten thousand species of birds. An attempt to see representatives of every species would be a fool’s errand. Some birds live in spots so remote, and in such low numbers, that they haven’t been seen in many years. New species are discovered quite regularly, making “all” a vanishing target. Many enthusiasts turn to the pages of field guides and handbooks, allowing the descriptions and illustrations to fuel their imagination of birds that they are unlikely ever to see.

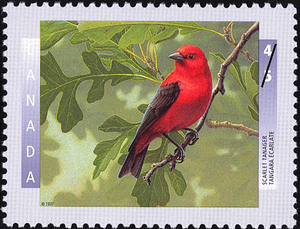

I did just that this week. I dived into my extensive ornithological library is search of birds that I had not stumbled across before. I skipped over some rather uninspiring birds, including the Brown Tanager and the Drab Seedeater, searching for beautiful creatures with exotic names. Here is what I found.

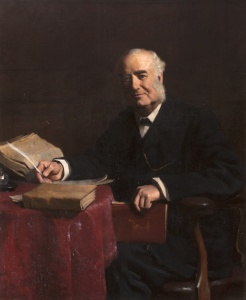

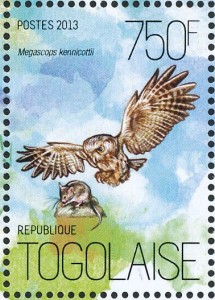

Painting of a Merida Flowerpecker by Joseph Smit – Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (vol. 1870, plate XLVI)

The Merida Flowerpecker was discovered in 1871. It can be found in the scrubby highlands of the Mérida region of Venezuela. A teeny songbird, it is sometimes displaced from good foraging spots by hummingbirds. Like hummingbirds, this flowerpecker feeds mainly on nectar and small insects. Both males and females are mostly black or blueish-grey on top, with reddish-brown undersides. The genus name, Diglossa implies that the bird has two tongues or has two voices, while the species name, gloriosa, is the Latin form of the word glorious. Even though we know almost nothing about the breeding biology of this species, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature considers the Merida Flowerpecker to be of least concern.

The scholarly community has known about the Red-collared Widowbird since the late 18th century. This bird has a wide, but patchy distribution across the southern half of Africa, and it is known to occupy a wide range of habitats. Roughly twice the size of a flowerpecker, female Red-collared Widowbirds are nondescript in their colouration. Males could scarcely be more impressive. Some are all black, but most have a bright red slash across their throat. Most impressive is the male’s black tail, which is longer than the rest of the bird in some subspecies. Males with the longest tails attract two or three mates, while more poorly-ornamented males remain unmated. Males and females both contribute to nest building, but incubation and feeding of nestlings are carried out by the females alone. The genus name, Euplectes, refers to their woven nest. The species name, ardens, is Latin for glowing or burning, likely a reference to the males’ bright red collar.

The Snow Mountain Mannikin was unknown to the bird world until 1939, when it was found at an elevation of more than four thousand metres in the Snow Mountains of west-central New Guinea. It is a perfectly respectable little songbird with a black face, light brown bib, darker brown back, striped sides, and a robust grey bill suitable for cracking small seeds. The genus name, Lonchura, refers to the pointed tail feathers of some members of the group. What really stands out about this bird is how little we know about it. The IUCN lists the Snow Mountain Mannikin as having a stable population, but that is something of a guess. We do not know if it resides on its breeding range year-round, or if it wanders widely. The nest is built of grass, but nothing else is known of its breeding biology.

And that is one of the most wonderful things about bird biology. Although we know a great deal about birds, much awaits our investigations.

Photo credits: Painting of a Merida Flowerpecker by Joseph Smit – Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (vol. 1870, plate XLVI) – https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%A9ridahakenschnabel#/media/File:DiglossaGloriosaSmit.jpg; Birds of Congo stamp collection, including a male Red-collared Widowbird – www.ebay.com; Snow Mountain Mannikin – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 107:

Now That We Understand the Problem…

11 November 2018

New Zealand Rockwrens are tough little birds. Living in high-altitude alpine habitat of New Zealand, their nests consist of excavated cavities within vegetated ledges, and cracks on cliff faces and boulders. At forty-four days, their nesting period is surprisingly long for a bird of that size. When confronted by a snowstorm during the breeding season, a parent may tunnel down through the snow to reach its chicks. Despite being warriors, could it be that New Zealand Rockwrens are helpless in the face of invasive mammalian predators?

If a plant or animals has been moved by humans from its native lands, across a natural barrier, and has managed to establish a self-sustaining population in that new spot, then it is considered to be “introduced.” If that species goes on to have negative consequences for the wildlife or landscape of its new home, or on human health or the economy, then the creature is considered to be “invasive.” A number of invasive mammals are causing trouble in New Zealand. These include stoats, house mice, rats and possums. Numbers of the New Zealand Rockwren have declined to the point where they are considered endangered. Are invasive, predatory mammals to blame?

Conservation biology Kerry Weston of New Zealand’s Department of Conservation and her colleagues studied the breeding biology of the New Zealand Rockwren, with particular emphasis on the potential impact of invasive mammals. At three high-altitude sites, Weston et al. searched for rockwren nests, and followed their progress. In some cases, nests were monitored using continuous video-recording and motion-activated cameras. Mammals were trapped and disposed of in some locales.

Weston and her crew located 146 rockwren nests, and reported on some interesting aspects of the birds’ breeding biology. For instance, both parents contributed to incubating the eggs and providing for the nestlings during the day, but females alone incubated eggs and brooded young at night. As the nestling grew in size, they received food every three or four minutes during daylight hours. Nestlings are noisy, and can sometimes be seen begging from the nest’s entrance.

The most common cause of rockwren reproductive failure was predation by stoats, rats and mice. Cameras revealed that stoats ate eggs, nestlings and brooding adults. However, in spots where predators were controlled, no predation by stoats was confirmed, and the leading cause of failure was nest abandonment, sometimes the result of extreme weather.

In their five-year study, just thirty-three stoats, ten rats and one mouse were captured. Despite the low number of mammalian predators in the landscape, it was clear that these animals had considerable negative consequences for populations of the endangered rockwren. The impact of invasive predators on insular and lowland bird populations is well established. Less well known is the effect of invasive mammals on birds breeding at high altitudes. Weston et al. wrote: “Novel predator control techniques that can be safely applied at scale above treeline are urgently required.” Let’s hope that such control will be forthcoming, and that the New Zealand Rockwren’s endanagered status will soon be changed.

Weston, K. A., C. F. J. O’Donnell, P. van Dam-Bates and J. M. Monks. 2018. Control of invasive predators improves breeding success of an endangered alpine passerine. Ibis 160:892-899.

Photo credits: New Zealand Rockwren stamp – www.pinterest.com; photograph courtesy of Pete McGregor - http://stmedia.co.nz/wgl-nzac/2011/02/have-you-seen-the-alpine-rock-wren/

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 106

With This Ring…

28 October 2018

It is hard to imagine that the field of astronomy would have made much headway if telescopes had never been invented, or that cell biology would have advanced far without microscopes. Even though the most powerful tool in any scientific endeavor is a curious mind, the application of technology helps too.

Those techniques do not always have to be sophisticated or expensive. In a marvelous example of understatement, Sanjo Rose and Dieter Oschadleus of the University of Cape Town in South Africa recently wrote: “Bird ringing provides novel insights into the private lives of birds.” Let me be a little less restrained; without the application of numbered bands to the legs of millions of wild birds, much of the lives of birds would still be a mystery to us.

Bird ringing, known is some parts of the world as bird banding, and the subsequent recapture of some of those banded individuals, allows us to learn about where, when and how they live their lives. Ringed on its breeding territory, a bird might be recaptured on its wintering grounds, providing us with a link between the two regions. If a combination of coloured legs bands are used for individual identification, we can sometimes follow a bird as it interacts with its environment and other birds around it.

It is almost certain that some readers of this column will be engaged in bird ringing as a hobby. I have met hobbyists that have ringed tens of thousands of birds. I have ringed a far smaller number of birds for research purposes. All of this activity contributes to a better understanding of the avian world. In southern Africa, the activities of bird ringers is coordinated by the South African Bird Ringing scheme. Since 1948, more than 2.3 million birds have had numbered rings applied to their legs.

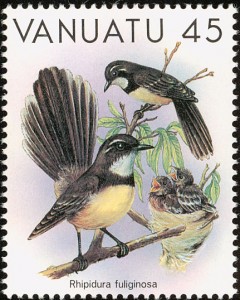

In a recent publication, Rose and Oschadleus reported on their efforts to learn about the longevity of estrildids, or waxbill finches, based on the banding and recovery of birds in southern Africa. Old World birds, estrildids can be found over large parts of Africa, southern Asia and Australasia. Within the group’s 130 species, some will be very familiar to fanciers of cage birds. These include the Australian Zebra Finch, Java Sparrow and Gouldian Finch. Rose and Oschadeleus found that more than 150,000 estrildids have been banded in southern Africa. Five species were represented by more than 10,000 ringing records each, including the Blue Waxbill and the Red-headed Finch. Many of those ringed birds have been recovered. Other species, including the Cinderella Waxbill and the Locust Finch have been ringed fewer than one hundred times, and none have been seen subsequently.

Longevity is a crucial demographic if we are to understand the population dynamics of species, and so Rose and Oschadleus reported those figures for southern African birds with the largest datasets. They found, for instance, that 27,813 Red-headed Finches had been marked, and that the oldest individual had been at least 5.2 years of age. More than twenty-thousand Bronze Manakins had received rings, but the oldest had been only 3.7 years of age. The record holder was a Blue Waxbill, one of 28,037 ringed. It had first been banded on June 25, 1996 and recovered on February 21, 2009. By my calculations, this bird’s minimum age was twelve years, seven months and twenty-eight days.

If you are involved in bird ringing, well done! You are contributing to a better understanding of birds. If you are looking for a new hobby, perhaps you will consider contacting the wild bird enthusiasts’ group in your area to find out how you could become part of the program.

Rose, S. and H. D. Oschadleus. 2018. Longevity summary from 69 years of Estrildidae ringing data in southern Africa. African Zoology 53:41-46.

Photo credits; Banding a Gouldian Finch fledgeling - ladygouldianfinch.com/features_banding.php; Cinderella Waxbill stamp - colnect.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 105

Hippy Birds

21 October 2018

Smooth-billed Anis are the late-1960s, commune-dwelling hippies of the bird world. Found as far north as the southern United States, and residing over much of the Caribbean and Central and South America, as many as six females lay their eggs in a shared nest. Ani chicks are raised by the group, with the help of multiple males and non-breeding helpers. It all sounds like a synergistic, happy-go-lucky love fest.

Closer examination shows that the situation isn’t quite so lovely as it appears. Communal they may be, but members of a Smooth-billed Ani group sometimes bury eggs, or roll eggs up the side of the nest and toss them out. There are at least two functions for this ovicidal behaviour. By destroying the eggs of others, a female can reduce the competition for limited resources for her own chicks. If she buries older eggs, or tosses older eggs from the nest, she helps to ensure that her chicks will not be the youngest in the nest. In doing so, her chicks will not be at a disadvantage because of competition with older chicks.

Leanne Grieves and James Quinn of McMaster University in Canada studied the ovicidal behaviour of Smooth-billed Anis in Puerto Rico. They explained that when they are first laid, ani eggs are white because they are covered with a thin chalky layer. When that layer wears away over a period of days, the underlying blue colour of the shell is exposed. Grieves and Quinn asked whether female anis might use the blue colouration of shells to indicate that the eggs had been laid some days earlier, and use that cue to eject or bury eggs when laying their own.

The researchers scraped some eggs with a small brush to wipe away the chalky covering, leaving them blue. In order to introduce a level of control, other eggs were handled, but the chalky covering was not removed, and so the eggs remained white.

Grieves and Quinn found that blue eggs were no more likely to be buried that white eggs. Blue eggs were also no more likely to be thrown from the nest. Colour does not seem to be a cue. However, they found that females in larger communal groups were more likely to engage in both of the destructive behaviours than females in smaller groups. In larger groups with four or five females, an egg was twice as likely to be destroyed as an egg in a group with just two or three females.

Given their size, female Smooth-billed Anis lay very large eggs; nearly 18% of their body weight goes into each one. An egg is a large investment. The greater the group size, the greater the competition. In order to make her investment of energy and resources worthwhile, it seems that females in larger groups will go to great lengths to ensure that her eggs, and therefore her chicks, are the ones to survive.

Life can be tough, even in a commune.

Grieves, L. A., and J. S. Quinn. 2018. Group size, but not manipulated whole-clutch egg color, contributes to ovicide in joint-nesting Smooth-billed Anis. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 130:479-484.

Photo credits: Smooth-billed Ani – www.pinterest.com; Smooth-billed Ani stamp - http://www.birdtheme.org/mainlyimages/index.php?spec=498

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 104

From the Wild, to Captivity, and Back

14 October 2018

Specialists in the field of biological conservation need to be simultaneously conservative and creative in their practices. When it comes to endangered creatures, we can rarely afford to be cavalier in using new, unproven methodologies. Even so, a technique that serve the needs of one threatened species may be entirely inappropriate for a different species. How can we be cautious and innovative at the same time?

It will be desirable to release animals to the wild after a period in captivity in several circumstances. For instance, individuals born in captivity, but released to the wild, may represent salvation for some species. Animals that have been confiscated by authorities may be used to bolster a declining wild population. It may be deemed useful to translocate individuals from a healthy wild population to an area from which the species has been eliminated.

Consider the Spix’s Macaw, native to northeastern Brazil. According to the IUCN, this Macaw is critically-endangered, and possibly extinct in the wild. With luck, the few individuals held in captivity will allow us to reestablish wild populations in the future. However, we don’t currently know the best way to ensure this. How do we obtain answers without risking the few individuals that are left?

Alice Lopes of the Instituto de Pesquisa e Conservaçăo in Brazil and her colleagues studied Blue-fronted Amazons that had been released to the wild after a period in captivity. The IUCN lists this parrot as of least concern. Lessons learned from releases of this reasonably common parrot might be applied to other, more-threatened species. The goals of Lopes and her colleagues was to “evaluate techniques of management and monitoring employed in the translocation of a group of captive-raised Blue-fronted Amazons.”

Thirty-one Blue-fronted Amazons were obtained from the Wild Animal Triage Centres (CETAS) in Brazil. Each had been in captivity for at least three years. These birds were studied at a site at a private farm in southeastern Brazil. Before release, the birds were trained to recognize predators. They were held in large aviaries that allowed them to practice the skills they would need to survive in the wild. After ten months of training, the parrots were permitted to leave, although they were permitted to return to the aviaries, and were provided with food to supplement what they found in the wild.

The thirty-one parrots released had a range of fates. Three were known to have perished. The whereabouts of five others could not be determined. Ten others showed behaviours that suggested they were adapting to life in the wild. The remaining thirteen individuals continued to behave in a way that better suited captive life, such as remaining near the aviary, and interacting with humans. It appeared that some members of the final group were captured by people in the area.

The study of Lopes et al. showed that “confiscated ex-pet Blue-fronted Amazon Parrots can be good candidates for translocation, but a training program should be applied to them prior to their release.” For instance, subjects need to learn to stay away from humans in order to avoid being recaptured.

Wild populations of the Blue-fronted Amazon range from Bolivia to northern Argentina. Even though it is considered to be of least concern, its numbers in the wild are in decline. According to the IUCN, between 1981 and 2005, 413,000 wild-caught individuals are known to have been sold internationally. Between 2008 and 2010, the CETAS of Brazil received 3,395 individual Blue-fronted Amazons, of which 2145 were seized. A quick search of YouTube will reveal why the Blue-fronted Amazon is so popular as a cage bird. It is to be hoped that will remain sufficiently common in the wild so as to continue to serve as a model for studies of conservation practices.

Lopes, A. R. S., et al. 2018. Translocation and post-release monitoring of captive-raised Blue-fronted Amazons Amazona aestiva. Acta Ornithologica 53:37-46.

Photo credits: Blue-fronted Amazon – fotolia.com & clipground.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 103:

Naughty Bird Biologists

7 October 2018

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology is a highly respected repository of information related to bird science. The most recent issue of the journal includes sixteen long articles and twelve briefer communiques. Readers of that issue can learn about research on the effects of flooding of the Missouri River on Least Tern reproduction, the nesting behaviour of Gray Tinamous in Ecuador, and parental behaviour of Costa Rican Clay-coloured Thrushes.

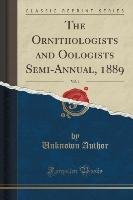

The journal began one-hundred and thirty years ago under the name The Ornithologists’ and Oologists’ Semi-annual. That title lasted only a year, being replaced by the more ponderous Semi-annual, Agassiz Association, Department of the Wilson Chapter. The name was changed to The Wilson Quarterly in 1892, and then The Journal of the Wilson Ornithological Chapter of the Agassiz Association in 1893. Things settled down after that, and the journal was called The Wilson Bulletin from 1894 to 2005.

In the early years, most subscribers to the journal were dedicated laypeople, rather than professional ornithologists. Articles from more than a century ago reflected the naive state of the field at the time. An account of birds seen while on a cruise might have been followed by an description of the timing of nesting of birds in a local cemetery. Even so those old issues can for interesting reading.

The second issue of the fifth volume of the journal was just eight pages long. On the second page of that issue was a statement short on details but rich in inuendo. It read: “Charges of sufficient seriousness have been preferred against Messrs. J. W. P. Smithwick and F. T. Pember to warrant their expulsion from the Chapter. A majority of the Executive Council have voted to remove their names from our roll. Their crime is fraudulent methods in Oology.”

It seems that J. W. P. Smithwick of San Souci, NC, and F. T. Pember of Granville, NY, had been active members of the group to that point, including writing articles with titles like: “Collecting in the Gila Valley” and “The Burrowing Owl: Speotyto cunicularia hypogaea.” Despite being on the membership list in Volume 5, issue 1, their names were missing from that list in issue 2.

I have not discovered what crimes against oology had Smithwick and Pember dismissed from the society, but I have found a few additional details about their comings and goings. Franklin Tanner Pember was born in 1841 and died in 1924. A businessman with interests in oil and oranges, his boyhood fascination with nature led to a substantial collection of artifacts, including bird nests and eggs. He and his wife, Ellen Wood Pember, established the Pember Library and Museum in 1909. That facility still serves the people of eastern New York state.

An online article by David Cecelski suggests that John Washington Pearce Smithwick was born in North Carolina in 1870, and was an avid collector of bird eggs by 1888. Shortly after being drummed out of the Wilson Society, Smithwick donated his collection of eggs to the state’s natural history museum. He then became a physician. I have not seen Cecelski’s reference material, and so cannot comment on his assertion that Smithwick was a hate-mongering racist.

Birds are angelic. Birds biologists will be judged by time.

Photo credits: Photo credits: reprint of The Ornithologists’ and Oologists’ Semi-annual Volume 1 (1889) – www.empik.com; image from page 61 of “The Ornithologists’ and oologists’ semi-annual” (1889) - https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14750528982/

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 102 -

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 102 -

The Early Bird

30 September 2018

Birds that migrate to far-northern latitudes for breeding may arrive to find a wealth of opportunity. Grazing geese are likely to find endless fields of fresh grass. Insect-eating pipits and wagtails may find their protein-rich quarry to be a non-depletable resource.

Bird biologists have found that the first individuals to return from their wintering areas to their northern breeding grounds generally have greater reproductive success. The causes of this success are many. The first birds back may have the greatest opportunity to recover from the challenges of migration, and could find access to the best breeding territories. If the first breeding attempt fails, early breeders have a greater opportunity to try again. Perhaps earlier males can increase their reproductive success by mating with females who are not their social mate. By breeding earlier, their chicks may have a longer period to grow and acquire the reserves necessary for successful southward migration.

It is possible, of course, that some birds will migrate northward too early, and will arrive to find their breeding grounds in the grip late-Winter weather. Even so, on the whole, earlier seems to be better.

However, as with so many aspects of bird biology, this phenomenon has been reasonably-well studied in species living in temperate zones, with far less information available for tropical species. Vanessa Bejarano and Alex Jahn of the Universidade Estadual Paulista in São Paulo, Brazil, sought to address that gap in our knowledge.

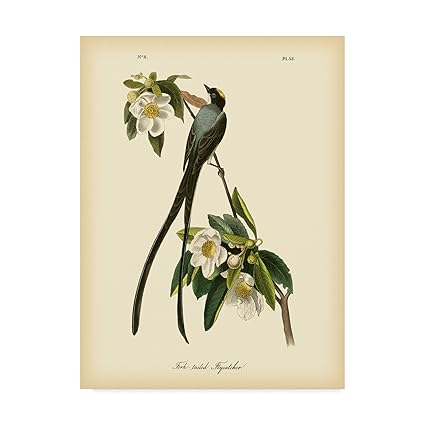

Between 2013 and 2016, Bejarano and Jahn studied a population of Fork-tailed Flycatchers in the Estação Ecologica de Itirapina in southern Brazil. Described as intra-tropical migrants, these flycatchers come to their breeding grounds from their off-season homes in northern South America. The birds were colour-banded for individual identification. The researchers monitored flycatchers on the study site, noting when they first arrived, and followed their breeding activities.

Life in the tropics can be challenging for birds, and Bejarano and Jahn found that only ten percent of nesting attempts were successful. On average, male flycatchers were seen on the breeding grounds earlier than females, a phenomenon known as protandry. Males that arrived first attracted females that laid eggs earlier. Nest success was higher when egg laying was earlier. In summary – earlier is better. Although this relationship between dates of arrival on the breeding ground and breeding success has been established for a number of birds in temperate regions, this seems to be the first study to show the association for birds that live within the tropics.

Further study will be needed to determine how male Fork-tailed Flycatchers manage to arrive to breed before females do, and why earlier arrival translates into greater success. The authors suggested that: “further research on the subject would benefit from a multi-disciplinary, comparative approach among migratory systems.” In an era of global climate change, the results of such research is likely to prove valuable.

Bejarano, V., and A. E. Jahn. 2018. Relationship between arrival timing and breeding success of intra-tropical migratory Fork-tailed Flycatchers (Tyrannus savana). Journal of Field Ornithology 89:109-116.

Photo credits: Brasilian stamp – www.pinterest.com; painting by John James Aububon – www.amazon.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 101 -

Endangered Birds on Refuse Sites

23 September 2018

As recently as 2009, the IUCN considered Africa’s Hooded Vulture sufficiently abundant as to be of “least concern.” Its status was downgraded to “endangered” in 2011, and dropped again in 2015 to “critically endangered,” and that is where this vulture sits today. It isn’t that Hooded Vultures are particularly hard to find; there are thought to be as many as 197,000 of them. All told, they have a comparatively large range in Africa, including many countries from Angola to Zimbabwe. Instead, the Hooded Vulture is considered to be critically endangered because of an extremely rapid decline in its abundance. According to the IUCN, this decline is the result of “indiscriminate poisoning, trade for traditional medicine, hunting, persecution and electrocution, as well as habitat loss and degradation.”

The bird might be rare elsewhere, but in recent years it seemed to be doing quite well in Ghana, where it was seen commonly in landfill sites, food markets, urban dumpsters and around slaughterhouses. In Ghana’s capital city, Accra, flocks of five hundred vultures might be seen. Then, at least according to anecdotal evidence, Hooded Vultures started rapidly decreasing in number.

The bird might be rare elsewhere, but in recent years it seemed to be doing quite well in Ghana, where it was seen commonly in landfill sites, food markets, urban dumpsters and around slaughterhouses. In Ghana’s capital city, Accra, flocks of five hundred vultures might be seen. Then, at least according to anecdotal evidence, Hooded Vultures started rapidly decreasing in number.

Francis Gbogbo of the University of Ghana, Japheth Roberts of the Ghana Wildlife Society, and Vincent Awotwe-Pratt of the Conservation Alliance saw the need for a critical examination of the Hooded Vulture’s abundance in its urban stronghold in Ghana, and an investigation of its principle sources of mortality.

The study was conducted in Accra. From just 377,000 residents in 1960, the human population of the city has grown to as many as 4,000,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Weekly counts of Hooded Vultures were made on the Legon Campus of the University of Ghana. As many as 220 vultures were seen between November 2010 and January 2011, but this number plummeted to just five individuals in 2015 and 2016. The numbers seemed to represent an actual decline, and not just a relocation. Some of the decline in vulture numbers may have been a result of competition with Pied Crows which increase in number on the university campus over the same period. The introduction of covered waste bins on campus may also have decreased the opportunity for scavenging by vultures.

Similarly, in an attempt to decrease the risk of collisions between airplanes and vultures, efforts were made to decrease the attractiveness of the region around Kotoka International Airport. For instance, refuse dumps in the area were closed or covered. The recent closure of unhygienic slaughterhouses in Accra likely also had an affect on Hooded Vulture numbers.

The researchers examined the published literature for details of the vulture’s abundance. Gbogbo et al. also spoke with vulture researchers, as well as those who had experience with the habitats frequented by Hooded Vultures, including waste managers, scrap dealers and refuse scavengers. It seems that the capture and sale of Hooded Vulture carcasses for use in traditional medicines and black magic is not insubstantial. The researchers found that the value of the head of a vulture in a market in Tamale was 200 Ghana cedis. That is about two-months’ wages for a middle-income earner in Ghana. Many dead vultures and vulture parts are apparently exported to Nigeria. Some vultures are being captured and sold as food, sometimes to an unsuspecting public.

Nothing about conservation of the Hooded Vulture is likely to be simple in Ghana. Clearly it is not appropriate to reopen refuse dumps in order to provide foraging opportunities. Gbogbo and his coworkers identified “the need for an intensive education of the Ghanaian populace on the significant status and need for the protection of the species.”

Gbogbo, F., J. S. T. Roberts and V. Awotwe-Pratt. 2016. Some important observations on the populations of Hooded Vultures Necrosyrtes monachus in urban Ghana.

Photo credits: Hooded Vulture photograph – www.pinterest.com; Hooded Vulture stamp - http://www.wnsstamps.post

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 99:

Hope

09 September 2018

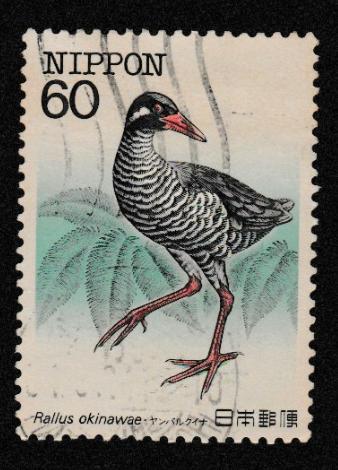

In the previous installment of A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, I described recent research on the natural history of the Okinawa Rail. Dr. Shun Kobayashi and his colleagues discovered, among other things, that this endangered rail is omnivorous, exploiting a wide range of plant and animal foods, and that they forage in more than one habitat.

Wanting to know more about the Okinawa Rail and other threatened wildlife in the area, I contacted Shun Kobayashi, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of the Ryukyus. He responded immediately with great energy and enthusiasm. He pointed out that the Okinawa Rail has become a symbol of Okinawan animal life. Consequently many people in the region are aware of the bird, but many of those are unaware of its plight. Predation by introduced mongooses and cats is likely the most serious source of rail mortality, but habitat loss and collisions with automobiles also contribute. The population fell through 2007, before beginning to recover.

Shun Kobayashi told me that the Ministry of the Environment became involved, creating a breeding program, and attempting to remove mongooses from northern parts of the island where their impact on native wildlife is greatest. Consequently, rails are becoming more numerous, although some threats remain.

Under the guidance of Professor Masako Izawa, university students continue to consider the natural history of Okinawa Rails. One student tracks individuals in the wild, and another studies captive individuals. The professor’s website describes other work that her group is engaged in. “We conduct research on mammal home ranges, environmental utilization, social structure, breeding behavior, feeding habits… Animals that students have researched… include the Iriomote wild cat, the Tsushina leopard cat, the flying-fox, Cervus nippon keramae, different types of mice, the blue rock thrush, and more.” The University of the Ryukyus has a very navigable website: http://www.u-ryukyu.ac.jp/en/.

Shun Kobayashi pointed out that Dr. Kiyoaki Ozaki, a researcher at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, has been studying Okinawa Rails for more than thirty years. You can learn more about the Yamashina Institute at: http://www.yamashina.or.jp/hp/english/index.html.

Shun Kobayashi explained that his interests were not just for our avian friends, but also for plant pollination systems that depend on mammals, and the ecology of animals that are found only in the Ryukyu Islands. He is, for instance, currently studying the impact of dogs and cats on the native animals of Okinawa-jima Island. I was told that the support of non-governmental organizations, such as the Conservation and Animal Welfare Trust, Okinawa, are key elements in the study of wildlife in the area. “I could not do the research without their support,” wrote Shun.

Despair only occurs when no hope remains. I see no need for despair for our natural world as long as people such as Dr. Shun Kobayashi, Professor Masako Izawa, and Dr. Kiyoaki Ozaki believe that there is a future.

Photo credits: Okinawa Rail successfully crossing a road – www.pinterest.com; map showing the location of Okinawa Rails – Yamashina Institute for Ornithology (http://www.yamashina.or.jp/hp/english/okinawarail/about_or.html)

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 98:

A Rail with a Future

02 September 2018

Recently I was discussing the Invisible Rail with a colleague. It is a rarely-seen bird that was first collected by Alfred Russel Wallace in the late 1800s. It is found on only the island of Halmahera in the North Moluccas of Indonesia. I explained to my colleague that the discovery of the Invisible Rail on a second island was something of a mystery given that the bird is presumably flightless.

“What makes you think that the Invisible Rail is flightless?” he asked. As a group, rails have a remarkable inclination to arrive on islands, loose their ability to fly, and then evolve into a form that is distinctive from other rails. If they have come to inhabit an island with no ground-dwelling predators, and lots of food on the ground, then flight is rather a waste of precious energy.

Since flightless rails on small islands often have small populations, and because recently-introduced predators are a common feature of islands, many rail species are under threat, and others have already fallen to extinction. Because so few ornithologists live on tiny islands, flightless rails are also a poorly-known group.

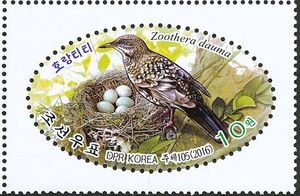

One of the very first requirements of a successful conservation program is a thorough understanding of the natural history of the threatened species. To this end, Shun Kobayashi of the University of the Ryukyus and twelve of his colleagues studied the diet of the endangered, almost entirely flightless Okinawa Rail. This bird is found only on the northern part of Okinawajima Island of Japan.

The IUCN’s description of the plight of the Okinawa Rail is not particularly optimistic. “This species is listed as Endangered because it has a single, very small population within a very small range on just one island, and both its range and population are undergoing continuing declines as a result of introduced predators and the loss of forest to logging, infrastructure development, agriculture and construction of golf courses.”

A through study of the diet of an endangered, ground-dwelling forest bird is not necessarily easy. Direct observation are likely to be hampered by the undergrowth, and sacrificing individuals to examine their gut contents is clearly not an option. Instead, Kobayashi and his co-workers examined the contents of the gizzards of 189 Okinawa Rails that had been killed by introduced Indian mongooses or traffic accidents.

The gizzards examined revealed a very large range of animals eaten, as well as eighteen species of plants. Among animal prey, four species of snails were particularly common. Insects, mainly beetles, grasshoppers and ants, also contributed greatly to the diet of these birds. The researchers did not hesitate to describe the Okinawa Rail as “omnivorous.” The study made it clear that these rails forage in more than one habitat type, as their gizzards contained millipedes from both open fields and forest edges, as well as hermit crabs that live on the coast. The abundance of land snails in the Okinawa Rail’s diet distinguishes it from other rails.

If Kobayashi and his colleagues had discovered that the Okinawa Rail had a particularly narrow diet, eating only the flowers of a very rare plant for instance, the bird’s long-term prospects might be less favorable. Finding that the rail is capable of exploiting a wide range of food types is one step forward in efforts to ensure the bird’s long term survival. In the next installment of A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, you will find more about the wonderful work being done to conserve Japanese wildlife.

Kobayashi, S., et al. 2018. Dietary habits of the endangered Okinawa Rail. Ornithological Science 17:19-35.

Photo credits: Okinawa Rail stamp – ww.lelong.com.my; art - amanaimages.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 97:

Greenlanders Can Breathe More Easily

19 August 2018

I read recently that there are more chickens than there are birds of all other 10,000 species of birds combined. That is a lot of chickens. I suppose it explains why virtually every article I find in scholarly journals relating to disease and pathology in birds concerns chickens. Of the very few studies that do not consider chickens, the vast majority are about turkeys. I was delighted to find a recent study of avian diseases that was about wild birds.

There is no doubt that the viruses responsible for avian influenza are a major concern. They have the potential to devastate poultry production (again, chickens!), and represent a serious potential threat to human health. Wild birds may play a role in the transmission and dispersion of avian influenza viruses to chickens and human populations, and may provide an opportunity for the evolution of viral agents. Anything that we can learn about avian influenza in wild birds may help us to combat future outbreaks.

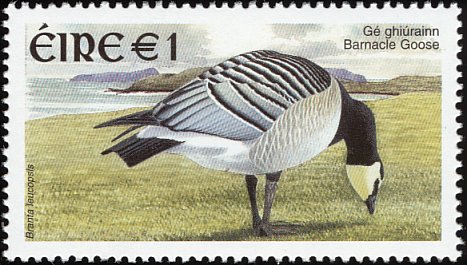

Migrating birds are a special concern. Infected individuals might move diseases over vast distances. Luckily, birds migrating in the world’s Eastern and Western hemispheres tend to remain separate, limiting their potential to cause a global epidemic. There is, however, an exception.

There are spots in the high Arctic where birds that winter in different hemispheres come together to breed in very large numbers. Northeastern Greenland is one such place. Tens of thousands of breeding Barnacle and Pink-footed Geese congregate in this region, where they are joined by migratory gulls, terns, waders and ducks of at least eighteen species. These birds have the potential to spread avian influenza viruses between Europe, Africa and North America. Furthermore, it has been suggested that in the cold of the far north, viruses excreted by breeding birds one year may survive to infect birds the following year.

French researcher Nicolas Gaidet and his colleagues visited Greenland’s Jameson Land, which they described as “a vast tundra area with scattered lakes.” They collected three hundred samples of fresh goose feces, and 28 feather samples from geese that were found in large flocks. Water samples were also taken from lakes that were home to breeding geese. Those samples were subjected to genetic analysis designed to detect avian influenza viruses.

The results of a study can rarely be summarized in a single sentence, but they were in the case of the study of Gaidet et al. “No AIV was detected in any fecal, feather or water sample tested.” Despite the high density of birds in the area providing an opportunity for transmission of avian influenza viruses, no evidence of it was found. This is, of course, good news. Particularly for chickens. Even so, the researchers pointed out that Greenland, as a crossroads for birds of different hemispheres, “warrants further surveillance for AIV in wild birds breeding or staging to better understand the role of high Arctic regions for intercontinental movements of AIVs.”

Gaidet, N., I. Leclercq, C. Batéjat, Q. Grassin, T. Daufresne, and J.-C. Manuguerra. 2018. Avian influenza virus surveillance in High Arctic breeding geese, Greenland. Avian Diseases 62:237-240.

Photo credits: Barnacle Goose – roaringwaterjournal.files.wordpress.com; Pink-footed Goose – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 96

House Sparrows in Kentucy

12 August 2018

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology is a respected repository of all matters pertaining to bird biology. In order to collect data worthy of publication in that journal, a researcher might have to spend years in crocodile-infested swamps or leech-filled jungles. The most recent volume of the publication includes articles on the breeding biology of Gray Tinamous in Ecuador, ovicide in Smooth-billed Anis in Puerto Rico, and assortative mating by Plain Laughingthrushes in China.

However, reports in the journal were not always so exotic. The original name of the Wilson Journal of Ornithology was the Ornithologists’ and Oologists’ Semi-annual. The very first issue was published in 1890. On pages 11 and 12 of that issue was an article entitled “Observations from the Deck of a Steamer” by Otley Pindar. A surgeon by profession, it seems that Pindar took a journey on the steamboat Granite State in the summer of 1889, embarking from Hickman, Kentucky. He sailed along both the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, spending his time on the ship’s upper deck watching birds, rather than sipping bourbon in the saloon.

Pindar provided readers of the O & O Semi-annual with his thoughts on seventeen species of birds he saw. Forester’s Terns, Chimney Swifts and Barn Swallows skimmed and darted near the boat, while Turkey Vultures circled high overhead. Downstream from Columbus, he spied a family of “Kingbirds,” which were almost certainly the species known today as the Eastern Kingbird. On the upstream side of Columbus, Pindar found Kildeers and “Snowy Herons,” which seems to be an old name for Snowy Egrets.

The dense swamps of Missouri provided roosting sites for American Crows, and Pindar spied what I suspect to be Fish Crows in both Shawneetown, Ill, and Lewisport, Ky. He encountered Great Blue Herons frequently as they flew across the river ahead of the boat. White-bellied Swallows, now known as Tree Swallows, entertained Pindar with their “aerial evolutions.” Riverside fields and forests were home to Common Grackles, American Robins, Eastern Meadowlarks and Field Sparrows. Henderson, Ky, gave Pindar the opportunity to see a very large colony of Bank Swallows and a covey of Northern Bobwhites.

Pindar was not able to identify every bird he saw, but those that he did seemed to have made his voyage all the more pleasant. Only one species of bird drew his ire. He wrote about the House Sparrow, an introduced species, describing it as “one which could be well dispensed with… found in abundance in every place at which the boat stopped, especially the larger towns and cities.”

In 1923, Pindar became the first ever president of the Kentucky Ornithological Society. He came upon this honor, in part, because he was judged to be the oldest practicing ornithologist in the state. The society is still around; its Fall 2018 meeting will be held the weekend of 14 to 16 September at the Pine Mountain State Resort Park. The House Sparrow is still around too, and can still be found in towns and cities. Pindar is long gone.

Pindar, L. O. 1890. Observations from the deck of a steamer. The Ornithologists’ and Oologists’ Semi-annual. 1:11-12.

Picture credits – stamp – www.birdtheme.org; photograph – www.pinterest.com

Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 95

Bald Eagles Aren’t Really Bald

05 August 2018

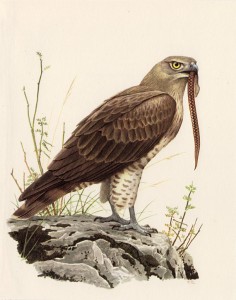

One of the greatest joys of being involved with the study of birds for a very long time is the opportunity to watch explanatory ideas unfold. An hypothesis that is accepted by one generation of bird biologists can be overturned completely by the next. For instance, when I was a university student, I learned that birds such as vultures and ibis had bald heads because it helped them to stay clean. If you spend your day with your head in garbage, or blood-soaked corpses, it could be challenging to keep your feathers in good condition.

It seems that that story is more complicated than that…

Birds with dark plumage probably benefit when their feathers absorb solar radiation. Darkly-coloured individuals likely spend less energy keeping warm than they would if they were lighter in colour. That is not the only potential advantage of dark feathers, but it seems to be one of the most important ones. However, at some times of the year, or at some times of the day, the heat absorbed by dark plumage might become too much of a good thing. Could it be that the bald heads of some darkly-coloured birds serve as radiators of excess heat?

Ismael Galván and his Spanish colleagues at the Doñana Biological Station in Seville and the University of Córdoba addressed the possibility that some birds are bald because it allows them to radiate heat when conditions get to warm. The group studied adult Northern Bald Ibises at Zoobotánico Jerez, a zoo and botanical garden in southern Spain. The body of this bird is covered completely in black feathers, except for a bald head which is red. The intensity of this red colouration can change rapidly when more blood is diverted to vessels close to the skin’s surface. The blood in these vessels would bring heat from the core of the body to the surface. All of this suggests that individuals might be able to use their heads as radiators to prevent overheating.

The study was conducted in July, the warmest part of the year in that region. Galván et al. collected thermal images of semi-captive ibises over a wide range of environmental temperatures. Over a range of conditions, it was possible to determine the temperature of the feathered parts of the body, as well as the temperature of the naked head. As these measurements were being made, the group also quantified the intensity of red colouration of each subject’s head.

The warmer the day, the warmer the bird. The warmer the bird’s head, the redder it was. “Norther Bald Ibises lost considerable heat amounts through the unfeathered head,” wrote Galván and crew. This radiation of heat continued until the environmental temperature rose to 35º C, about 95º F, after which the radiator was no longer effective. The researchers are not currently able to say whether the increased flow to the skin of the head when the birds warms up is the result of a simple physiological response, or whether the bird is able to control the radiator.

This line of inquiry might be extended to include other species of bald birds, including the Bald Starling (aka Coleto), the Bornean Bristlehead, the Bald (Noisy) Friarbird, and the Bald Parrot. However, the study would be pointless on Bald Eagles, because…

Galván, I., D. Palacios and J. J. Negro. 2017. The bare head of the Northern Bald Ibis (Geronticus eremita) fulfills a thermoregulatory function. Frontiers in Zoology 14:15.

Photo credits: www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 94

A Sinking Feeling

29 July 2018

Some numbers are so large as to be almost impossible to comprehend. For instance, China’s farmlands occupy 1.3 million square kilometres, more than half a million square miles. To put that value in perspective, it is more than two-and-a-half times the land area of Spain. Lots of mouths to feed require lots of land for crops. All of that farmland provides for the needs of some birds, but not others.

The story of the exploitation of resources becomes a bit more complicated when we read that 40% of farmlands in China are underlain by deposits of coal, a precious commodity. The extraction of coal in China has resulted in subsidence of land on a very large scale. This subsidence has required the abandonment of many rural agricultural villages, and relocation of the people who lived there.

Chunlin Li and colleagues at Anhui University and the Ministry of Environmental Protection studied the impact of land subsidence and the abandonment of rural villages in areas with coal mining on the abundance and diversity of birds. They conducted their study in the Huaibei Plain in the North China Plain, an region important for both farming and coal mining. In this region, the area affected by subsidence was growing at a rate of more than twenty square kilometres each year. When villages were abandoned because of subsidence, they were generally left as they had been.

Li et al. compared birdlife in inhabited villages and abandoned villages, counting birds that were seen or heard. The researchers were interested in both bird abundance and diversity, but also the structure of vegetation in the two habitat types. They found that abandoned villages had greater cover by shrubs and grasses, with more layers of vegetation. Field surveys documented more than 9,000 birds of 47 species. Abandoned villages were home to nearly twice as many birds and twice as many species as those villages that were still inhabited. Among birds that were more likely to be seen in abandoned villages were Common Hoopoes, Grey-capped Greenfinches, White Wagtails, and Long-tailed Shrikes.

The simplest messages might be that coal mining led to land subsidence, which led to abandonment of villages, which led to a greater abundance and diversity of birds. However, a curious thing happened to villages that had been abandoned because of subsidence. Abundant rainfall, combined with a high groundwater table, meant that after a few years, land that has collapsed because of coal mining turned into ponds, reservoirs and small lakes. Birds that had been taking advantage of abandoned villages would soon be replaced by wetland species. For some species, the opportunities provided by village abandonment would be short-lived.

Li,C., P. Cui, S. Zhou and S. Yang. 2018. How do farmland bird communities in rural settlements respond to human relocations with land subsidence induced by coal mining in China? Avian Conservation and Ecology 13(1):6.

Photo credits: Grey-capped Greenfinches, photograph by John Fish (right) and White Wagtail (bottom) – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 93

A Place Where Many Herons Come

20 May 2018

I like simple definitions. According to the Gage Dictionary of Canadian English, a heronry is: “a place where many herons come in the breeding season.” Perfect. It seems that Ramesh Roshnath and Palatty Alesh Sinu of the Central University of Kerala like definitions to be a little more comprehensive. To them, a heronry “is group nesting of colonial waterbirds” which might include herons, storks, pelicans, cormorants, ibises, and spoonbills, which cluster their nests in time and space.

Roshnath and Sinu had the right to claim that their definition is closer to the mark, as they have been studying the avian residents of heronries of the Kannur and Kasaragod regions of southwestern India. The waterbirds that nest in heronries in this region include Little and Indian cormorants, Little, Intermediate and Great egrets, Oriental Darters, and both Purple and Grey Herons.

We all recognize that the conversion of intact operating native habitat into urban settings is not going to stop. Does that conversion need to be completely devastating to native wildlife, or is sustainable development possible? Roshnath and Sinu set out to document the impact of urbanization on colonial waterbirds, with the hopes of finding ways to make the lives of these birds as productive as possible.

The researchers found fifty-two heronries in spots which included wild regions such as mangrove inlets, but also in trees adjacent to roadways, and in urban and residential sites. They visited the sites at the peak of the breeding season, counting and identifying birds’ nests, and recording details of the nesting trees such as species, height and diameter.

It was no surprise to find that some of the waterbirds nested more frequently in wetlands habitat than in cities. These birds included Purple Herons and Great Egrets. Curiously, some birds were more likely to engage in breeding in trees in city landscapes, including Black-crowned Night Herons and Little Cormorants. Over 1,500 nests were documented in trees along major roadways, but fewer than 500 in mangrove trees. Just 285 nests were seen in trees at forts and temples, and eighty in residential areas. The most popular trees for nesting were rain trees, which are highly valued as urban shade trees. Rain trees provide the birds with materials with which to construct their nests, and a branching patterns that facilitates nesting. Also popular with the birds were copper pod trees, jackfruit, mangoes, and banyan trees.

Beyond abundant suitable nesting trees for waterbirds, it seems that the urban environment in this part of India provides reduced predation pressure from snakes and birds of prey. Further, urban fish markets may provide waterbirds with part of their diet in the breeding season.

Some heronries in this part of India have likely been in use for a very long time. The continued use of some of these sites is not certain. Trees that are centuries old are felled to allow for the expansion of roads. Birds abandon heronries when bridges and fly-overs are built at the level of the tree canopy.

When it comes to sustainable development, simple solutions are often the best. “Posters regarding the nesting birds species could be posted under the trees to draw public attention and create awareness,” wrote Roshnath and Sinu. “Local governments may consider erecting heronry guards above the bus waiting shelters if nesting trees are located in such places.” If trees need to be felled for a city’s expansion, workers might selectively remove non-nesting trees first.

By these means might herons (and other waterbirds) continue to use traditional heronries.

Roshnath, R., and P. Allesh Sinu. 2017. Nesting tree characteristics of heronry birds of urban ecosystems in peninsular India: implications for habitat management. Current Zoology 63:599-605.

Photocredits: Oriental Darter and Purple Heron with chicks – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 92

The Single Best Solution

06 May 2018

When it comes to finding the single best solution to a challenge, I suspect that there are few challenges greater than those faced by parent birds. If the best solution is the one that will allow a parent to make the greatest possible genetic contribution to following generations, then the questions to be answered are nearly endless. Shall I attempt to mate monogamously, polygamously, or promiscuously? If I mate monogamously, how much of an effort should I make, and how much work shall I leave for my partner? Shall I put all of the year’s efforts into a single breeding effort, or shall I try to breed twice? Is it best to remain faithful to my partner, or to cheat? What is the best solution?

Japanese Tits are tiny songbirds that breed, not surprisingly, in Japan, as well as in surrounding parts of mainland eastern Asia. They are short-lived, and are socially monogamous. They lay their eggs and raise their nestlings in cavities, and will utilize nestboxes if given the opportunity. Many pairs will attempt to raise two broods in a year, rather than just one. Given that the average lifespan of a Japanese Tit is just two years, a second brood is likely to greatly increase an individual’s lifetime reproductive success.

Daisuke Nomi, Teru Yuta and Itsuro Koizumi of Hokkaido University and Niigata University in Japan studied the breeding behaviour of Japanese Tits in the Tomakomai Experimental Forest of Hokkaido for three years. The researchers were particularly interested in the effort that male tits made in provisioning their young. A male that makes a great effort to feed his chicks may realize greater reproductive success, but not if his partner responds by reducing the effort she makes. If a male makes a greater number of feeding trips this year, he may wear himself out and have a lesser probability of surviving to breed again next year.

Or… Could it be that a male that makes a particularly great effort in the year’s first breeding attempt will free his mate to recover from the stresses of breeding, and so increase the chances that she will be able to breed a second time?

Nomi and his colleagues utilized two Japanese Tit breeding sites, each provisioned with 150 wooden nestboxes. These boxes were checked frequently to document laying date and the number of eggs in each nest. Parents at each nest were marked with coloured and numbered leg bands. Both parents and their chicks were weighed, and the length of their legs measured. The rate at which the parents provided food to the chicks at each nest was determined using video cameras.

The greater the number of feeding trips made by the male, the greater the mass of the chicks in that nest. Beyond that, pairs in which the male made a high contribution were more likely to make an attempt to breed a second time in the same year. Ultimately, the decision about whether to make a second breeding attempt is very likely made by the female. Her decision seems to be made, in part, on the basis of the work ethic of her partner. “Paternal care may be more influential than previously though,” wrote Nomi et al.

Given the obvious advantage of making a large contribution to nestling care, why do not all males feed their chicks as fast as they possibly can? A male that spends all of its time and energy feeding chicks may be spending less time on essential defense of the breeding territory. If a male doesn’t give himself a break occasionally, he may diminish his chances of surviving until the following year. A male with a bit of free time may try to engage in copulations with females on neighbouring territories, and so spread his genes that way.

When it comes to birds and reproduction, the single best solution may not be as simple as it might seem.

Nomia, D., T. Yuta and I. Koizumi. 2018. Male feeding contribution facilitates multiple brooding in a biparental songbird. Ibis 160:293-300.

Photo credits: Japanese Tit stamp - www.birdtheme.org; Japanese Tit photograph – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 91

The North Wind Doth Blow

29 April 2018

Some bird species have an incredibly small distribution. Consider, for instance, the Helmeted Honeyeater. The state bird of Victoria, Australia, very small numbers of this bird can be found in the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Area, and almost nowhere else.

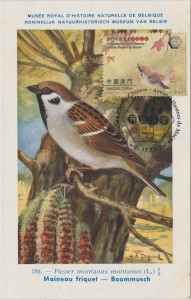

At the other end of the distribution scale are bird species with ranges that almost defy belief. One such bird is the Eurasian Tree Sparrow which can be found from Afghanistan to Brunei; from Christmas Island to Iraq; from Japan to Ireland. Beyond its native distribution, Eurasian Tree Sparrows have been successfully introduced to far-flung lands including Canada, southern Australia and the Philippines, and are sometimes seen in Israel, Gibraltar, and Timor Leste. These sparrows are clearly incredibly flexible and tolerant. However, the flexibility and tolerance of no creature is infinite.

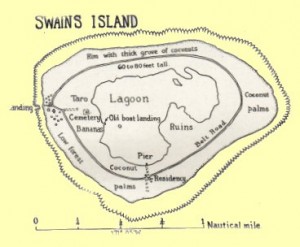

Sixteen kilometres off the north tip of Western Australia, Troughton Island has a permanent human population of just two. It is less than one km2 in area, and although the island has an airport and an automated weather station, it has no standing drinkable water. Is it the sort of place where a population of Eurasian Tree Sparrows might persist?

Between 6 and 8 August, 2016, a survey of sea turtle nesting on Troughton Island was conducted by Uunguu Rangers from the Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation and staff of the Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife. At that time the island’s resident caretakers, Brad and Heather Newman, pointed out four small sparrows foraging in the grass near the airstrip. These were later identified as Eurasian Tree Sparrows. Another expedition later that month found these four sparrows drinking from a dripping air conditioner. Three of the four sparrows were killed. The two carcasses that could be retrieved were tested for avian influenza, and found to be free of the disease. The fourth sparrow was not seen after September of 2016, and had presumably died.

An earlier caretaker on the island, Peter King, had reported as many as seventeen Eurasian Tree Sparrows on the island in 2011 following a storm. King noted that some of the birds had bred.

Reporting on these events, Anton Tucker of the WA Department of Parks and Wildlife and his colleagues speculated on the origin of the Eurasian Tree Sparrows on Troughton. The closest population of this sparrow to Troughton Island is four hundred kilometres away in Indonesia. This bird species is thought to periodically take up residence in new lands after hitching rides on large ships, and virtually all earlier records of this species in Western Australian have been associated with ports. However, this form of dispersal seems unlikely in the case of the sparrows on Troughton Island. The island cannot accommodate large cargo ships, and is visited infrequently by supply ships. Instead, the seventeen Eurasian Tree Sparrows first seen on Troughton Island in 2011 were likely blown there by a substantial storm.

According to the Australian Bureau of Meterology, Cyclone Carlos blew across the north and west coasts of Australia between 13 and 26 February, 2011. Very heavy rains caused widespread flooding and damage to roads and properties in and around Darwin, and forced the evacuation of the community of Nauiyu.

Beyond heavy rains, the cyclone may have also brought sparrows from the north to Troughton, if only for a time. The lack of available drinking water, combined with the presence of predatory Children’s pythons almost guaranteed that the plucky Eurasian Tree Sparrow would not survive on the island indefinitely.

Tucker, A. D. 2017. Invasive Eurasian Tree Sparrows Passer montanus on Trougton Island in the North Kimberly of Western Australia: a cyclone-induced colonization attempt? Australian Field Ornithology 34:67-70.

Photo credits: Eurasian Tree Sparrow Macau photograph – www.pinterest.com; stamp – www.bird-stamps.org

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 90 -

Bearded Vultures are Rebounding

22 April 2018

Large animals face big challenges in the modern world. Their need for abundant resources, often spread thinly, may require undisturbed habitat over a vast area. These requirements can put large creatures in conflict with the activities of humans. It may be much easier to conserve populations of shrews than of whales; of geckos than of crocodiles.

Even though Bearded Vultures have a comparatively wide range across Europe, Africa and Asia, breeding populations are often quite small, and with a spotty distribution. This large vulture is not considered to be endangered, but the IUCN does consider it to be near-threated, and with a declining population.

In the late 19th century, these birds were exterminated in the Alps of Europe. Almost a century later, efforts to reintroduce Bearded Vulture to the Alps proved successful. These efforts began in 1986, and thirty-seven individuals were released between 1991 and 2008. The first successful breeding was seen in 1997, and the population began to grow.

It is crucial to document the whys and wherefores of reintroduction efforts, whether successful or not, because these can help direct future efforts of a similar kind. We need to build on our successes, and avoid making the same mistakes twice. To that end, David Jenny of the Swiss Ornithological Institute and his Swiss and Italian coworkers set out to record the demographics of the reintroduced population of Bearded Vultures in the Central Alps. The study area comprised 6000 km2 of mountains and valleys, 500 and 4000 metres above sea level. The team sought vulture territories, and document breeding between 1997 and 2015. Hundreds of volunteers contributed observations made on formal surveys.

By 2015, nine breeding pairs of Bearded Vultures were known from France, along with ten pairs in Italy, twelve pairs in Switzerland, and three pairs in Austria. These breeding pairs, nesting on cliffs, had a clumped distribution that seemed to radiate outward from the original release sites. Even though young vultures, born in the wild, may travel very long distances on exploratory trips, they tend to return to the region of their birth when they are old enough to breed. Many new pairs establish territories further and further from the original release sites, and so the increase in population number also means an increase in the species’ range in the Alps.

Although emigration from the study site to distant sites appears to be low, and the population may face inbreeding problems in the future, reintroduction of the Bearded Vulture in Alps must surely be considered a success worthy of celebration. So many vultures occupied the Alps by 2008 that authorities were able to stop introducing new birds from captivity. Jenny et al. wrote: “Overall, the nucleus in the Central Alps contributes substantially to the resettled and growing Alpine population of the Bearded Vulture.” Well done.

Jenny, D., M. Kéry, P. Trotti and E. Bassi. 2018. Philopatry in a reintroduced population of Bearded Vultures Gypaetus barbatus in the Alps. Journal of Ornithology 159:507-515.

Photocredits: Bearded Vulture photograph and stamp – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 89:

Urban Ornithology

08 April 2018

Last year, while on a trip to Faro in southern Portugal, Sarah and Michael Farn had the opportunity to eat breakfast on the rooftop of their hotel while watching a pair of White Storks tend to their chicks. The nest, roughly constructed of large sticks, was situated on the rooftop of a church. Sarah wrote to me to ask how often this species of stork nests in the heart of cities in Europe.

Well, Sarah, it seems that White Storks are perfectly pleased to nest in and around human settlements, and that the association between humans and storks may date back to the Neolithic period. In a recent publication, Grzegorz Kopij of the Wrocław University of Environmental Life Sciences revealed quite a lot about this interaction in Poland.

The city of Wrocław appears to have a lot going for it. The community has nearly 650,000 residents, and a history that dates back well over 1000 years. It is home to many fine universities with a combined population of more than 130,000 students. Wrocław lies in a valley where four smaller rivers join the large Odra River. From Kopij’s description, it seems that the city and surrounding countryside is a marvelous amalgam of grassland, forests and recreational area. Regrettably, the air is among the most polluted in all of Europe, but otherwise it sounds like a pretty neat place.

The storks certainly seem to think so. Two nests were located within a kilometre of the city centre. Surveys of nests in Wrocław demonstrated considerable variation among years, with just five nests in 1999, but nineteen breeding pairs in 2004. Kopij attributed some of this variation to the availability of foraging opportunities. When grass was mowed along the city’s river systems, the breeding population increased, but fell again when the grassland was left to grow wild. It seems that years with good rainfall resulted in more food for the chicks than in drier years. On average, White Stork nests in Wrocław raised 2.65 chicks, just a shade less productive than nests in rural settings.

Kopij found that Wrocław is the only Polish city with a population in excess of 100,000 residents to have a large population of nesting White Storks. He believes that modest management of the landscape around cities could have a positive influence on this species. Describing the bird as a charismatic species, Kopij suggested that White Storks: “may attract attention of naturalists, ecologists and conservationists in urban environments, (and) facilitate directly citizen engagement with nature, environmental education and awareness.”

If you are like Sarah, and would like me to write a column about a type of bird that really interests you, or would like to know more about a particular topic in bird biology, please be in touch with me at glen@glenchilton.com.

Kopij, G. 2017. Changes in the number of nesting pairs and breeding success of the White Stork Ciconia ciconia in a large city and a neighbouring rural area in South-West Poland. Ornis Hungarica 25:109-115.

Photo Credits: www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 88:

Which One is Not a Real Study of Birds?

01 April 2018

In the spirit of the first day of April, I present a challenge. Below you will find descriptions of three studies. Your task is to deduce which two studies described are legitimate, and which one is made up. Are you ready?

Study Number One:

It is no surprise to anyone that many species of birds migrate long distances between their breeding grounds and spots where they spend the non-breeding season. Snails, on the other hand, are almost perfectly constructed to stay exactly where they are. Until…As part of a long-term study of migratory birds in Louisiana, researchers routinely captured, measured and banded songbirds in forested habitat near Johnson Bayou. On their northward spring migration, large numbers of birds use this spot after crossing the Gulf of Mexico. Each captured bird was inspected thoroughly. The assessment of an Indigo Bunting revealed a number of snails attached to the bird’s breast, buried beneath its feathers.

If you suspect that this description is the phony, then you are mistaken. In a paper published in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology in 2017, Theodore Zenzal, Emily Lain and Michael Sellers of the University of Southern Mississippi concluded that small, hitchhiking snails may be able to take advantage of songbirds to travel great distances, expanding their ranges and colonizing previously unoccupied spots. Transportation of this sort could have serious ecological consequences if exotic species arrive, establish themselves, and become invasive.

Study Number Two:

Males of some species of birds, but not all, have a penis. Some of these penises are pretty impressive; I will leave it to you to search for information on the Argentine Lake Duck. Within a single species of duck, there is considerable seasonal variation in penis length; they become longer in spring, and shorter after the breeding season. However, not all drakes are equally well endowed. What factors promote the genitalia of some males over others? Could it be that a surplus of males would cause each male to grow a longer penis?

Ruddy Ducks and Lesser Scaup were studied in captivity in Connecticut. Females were housed either with a single male, or with multiple males, establishing a competitive situation. When faced with competition for mating opportunities, drakes grew longer penises than did those with a hen all to themselves. The situation was more complex among Ruddy Duck drakes. Males in groups grew their penises more quickly, but maintained that length for a briefer portion of the breeding season.

If you picked this study as the sham, then you would be incorrect. Patricia Brennan of Mount Holyoke College and her coworkers published the results of their study of Lesser Scaup and Ruddy Ducks in 2017 in the journal The Auk. It is possible that a longer penis allows a drake to deposit his sperm deeper in a hen’s reproductive tract, which could be important when males are competing with each other. The authors described the genital size of male Ruddy Ducks as “extreme,” and their mating system as “promiscuous.”

Study Number Three:

That leaves only the third study, right? Consider calcium carbonate. This chemical compound is found in three states. One of these, calcite, makes up the bulk of bird eggshells. A different state of calcium carbonate, called vaterite, is rare in nature, probably because it is not a particularly stable compound. Among the places that it can be found is kidney stones and gall stones. It can also be found as a thin, chalky layer on the outside of eggs of some bird species. That layer doesn’t seem to prevent water loss across the egg’s shell. Could it be that vaterite helps prevent shell breakage when two eggs bump into each other?

“Vaterite” doesn’t even sound like a real word, and yet, once again, the study described was completely legitimate. Steven Portugal of Royal Holloway University of London and his colleagues studied vaterite on the shells of the Greater Ani, a large and beautiful cuckoo from Central and South America. In a 2017 article in the journal Ibis, the researchers explained that that when two Greater Ani eggs bump into each other, the dent that results is less than the thickness of the vaterite layer. These findings suggest that the role of vaterite, at least in Greater Anis, is to make eggshells less vulnerable to fracturing

Just because something seems unlikely, that doesn’t make it untrue. Keep that in mind this April Fool’s Day.

Photo credits: Indigo Bunting stamp, Ruddy Duck and Greater Ani – www.pinterest.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 87

Birds That Provide Ecological Services

18 March 2018

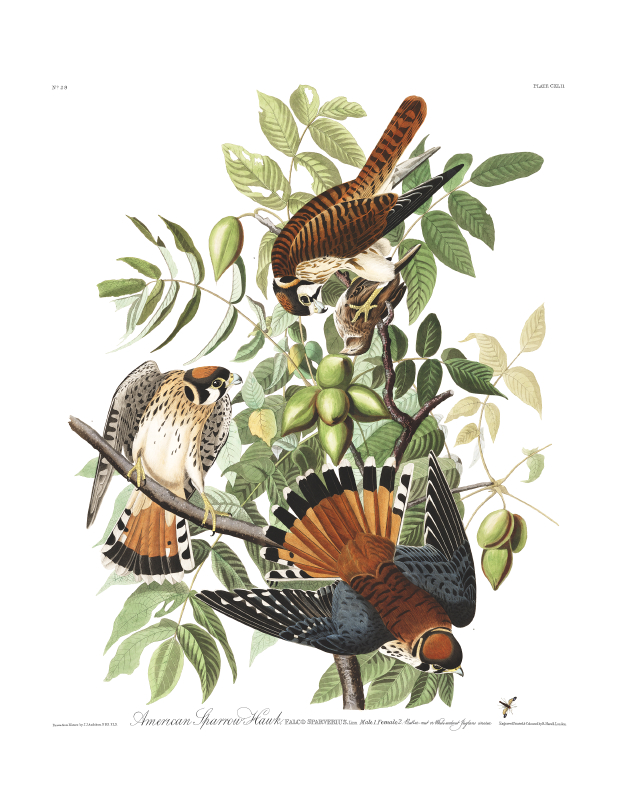

In response to a question from reader Ellen Gasser, last week’s entry considered declining populations of the American Kestrel, Falco sparverius. Another reader of A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, John Cunningham, wrote to me this week, asking if I could write another piece about recent advances in our understanding of American Kestrels. John is a recent convert to the world of birds, and that little bird of prey was one of the first new birds he learned. I discovered a 2017 publication by Megan Shave and Catherine Lindell of Michigan State University that seemed particularly relevant.

In our attempts to keep the ever-increasing human population well fed, more and more original intact operating ecosystems are being turned over to agricultural land. This sort of conversion generally results in a landscape that is less complex than the habitat it replaced. For birds, one the greatest difficulties is the destruction of nesting opportunities, such as nesting cavities in old trees.

And this is where American Kestrels comes in. The diet of these birds consists mainly of insects and small birds and mammals, many of which are pests in orchards. These kestrels nest in cavities in trees. If insufficient natural opportunities exist, perhaps they would be willing to utilize artificial nest boxes. However, it would be unreasonable to expect the owners of orchards to erect nest boxes without providing evidence that kestrels will use them.

Researchers Shave and Lindell surveyed American Kestrels in a fruit-growing region of northwest Michigan which lacks suitable natural nesting cavities. The researchers hypothesized that sites with nest boxes would be more likely to have the beneficial kestrel in residence. Were they correct?

In the study area, American Kestrels took up residence in 93% of newly-erected nest boxes, and these nests were successful in 91% of cases, producing an average of four fledglings per nest. Nest boxes that were not used were probably too close to other nesting pairs. Of the food provided to the chicks, 81% were arthropods, and 13% were small mammals. Good news!

The publication of Shave and Lindell had a great number of other details, including methodology, the specific results of surveys, and mathematical modelling of data, but all of that distills to a simple message. American Kestrels, at least in this fruit-producing region of Michigan were more likely to colonize and persist at sites to which nest boxes had been added. The authors went on to say that: “Increasing kestrel presence in and around orchards could enhance ecosystem services provided by kestrels.” Most earlier studies of birds of prey in agricultural landscape have focused on Barn Owls, and a broader understanding is bound to be valuable.

With luck, John, many orchard owners will respond to this study by providing nesting opportunities to American Kestrels.

Shave, M. E., and C. A. Lindell. 2017. Occupancy modeling reveals territory-level effects of nest boxes on the presence, colonization, and persistence of a declining raptor in a fruit-growing region. PLoS One 12 (10): e0185701.

Photo credits: Audubon illustration of American Kestrels - auduboneditions.com; American Kestrel in nesting box - http://www.birdwatching-bliss.com

A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers, Article 86:

Birds of Prey in Challenging Times

11 March 2018

I recently asked readers of A Traveller’s Guide to Feathers to write to me, suggesting topics or species about they would like to know a little more. Ellen Gasser wrote to ask about populations of American Kestrels, saying: “My feeling from personal observation is that they are far less abundant in farm/ranch areas of Alberta than 30 years ago.” Here is what I found, Ellen.

My first port of call was the website of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and their Red List of Threatened Species. According to the IUCN, the American Kestrel is of “least concern” with a population that is apparently stable across its very wide distribution. These birds have a vast range across North, Central and South America. That doesn’t sound too bad at all.