Falling Down the Thames Blog 47, 04th February 2015

Splash!

My mind finds funny ways to entertain itself. Of late, I have been trying to think of great cities that are situated on neither a river nor a sea. It hasn’t been easy. The Canadian city of Regina in Saskatchewan is on a creek, but not a river… I’ve been to Bozeman, Montana, and I didn’t see a river…

There is a really good reason for the union of cities and major bodies of water, of course. Rivers and seas are opportunities for transportation and recreation, for the dumping of waste, and the extraction of water for all sorts of purposes.

London, a great city, is not only situated on a great river, the Thames, but it has all sorts of smaller rivers running through it. I described some of these “lost” rivers in an earlier blog. But is London in the very best location relative to water? Possibly not.

New Scientist is a weekly magazine dedicated to keeping readers up to date on the latest and greatest findings in the fields of Astronomy, Physics, Mathematics, Biology, Chemistry and Engineering. I have been reading the magazine for thirty-five years, and feel that my grasp of fundamental scientific and engineering principles is all the better for it. Of late, contributors to New Scientist have been engaged in a dialogue about the relationship between Britain and the surrounding sea, and the mounting threat that the sea poses to the city of London in particular.

Human-created global climate change is threatening costal lands, including London, in two ways. First, as the water locked up in retreating glaciers is released to the sea, the surface of the ocean rises. Not a lot, but enough to make a difference. Also, because warmer water occupies a great volume than cooler water, “global warming” is causing the sea to rise even more.

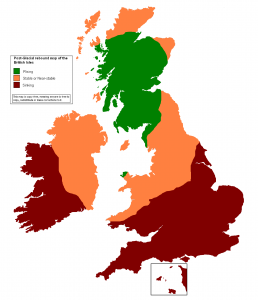

That isn’t the end of it for poor old London. In millennia past, when thick glaciers sat over vast parts of northern North America, Europe and Asia, the weight of the ice pushed the land downward. With the retreat of those glaciers at the end of each ice age, the land sprung back up in a process known as isostatic rebound. This rebound isn’t just a thing of the past, but continues slowly to this day. As a result, Scotland is gradually getting higher. In a teeter-totter kind of effect, the south of England is gradually getting lower.

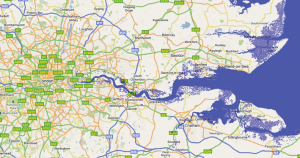

But there is more. Geologically speaking, the Thames Valley is a syncline, a downward-folding bit of landscape that, in the very long term, will continue to get lower and lower. Further, until recently groundwater was drawn from the earth below London to provide for the needs of the great metropolis, which has caused the land to sink further. And if that weren’t bad enough, a quick look at a map of England will show that the North Sea forms a sort of funnel, with London at the pointy end. Storms tend to push vast volumes of water up the Thames Estuary.

New Scientist reader Hillary Shaw summarized the situation this way: “All this adds up to one inescapable fact: the lower Thames was not a good place to site a major capital city.”

In a later blog, I will describe one of the mechanisms by which London tries to defend itself against the sea. It is a mechanism through which Krista and I will paddle in a couple of months from now.

- Glen

Photo credits: London on the River Thames – www.gbposters.com; Post-glacial rebound in British Isles – www.wikipedia.com; map of London and the Thames estuary - www.thamesestuary.com; London bridge suffering a virtual storm surge – www.floodlondon.com